Bubble Cards – 1720

The headlong Fools Plunge into South Sea Water/ But the sly Long-heads Wade with Caution a’ter/ The First are Drowning but the Wiser Last/ Venture no Deeper than the Knees or Wast

In these cards are contain’d & represented 52 Bubbles, answering to every Card in the Pack, with a Satyrical Eppigram upon each by the Author of the South Sea Ballad.

(Text on the packaging of the Bubble Cards)

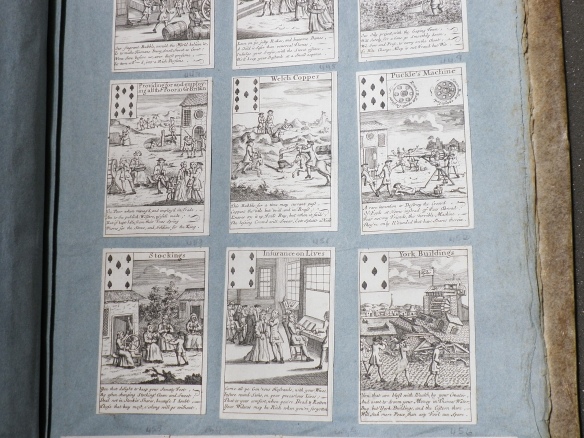

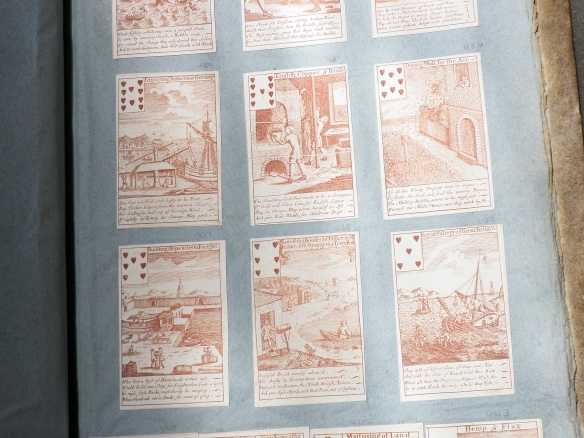

Our treasure for this month is a pack of playing cards from 1720. Known as the ‘Bubble Cards’, this collection of satires was printed for Thomas Bowles, printseller, at the height of the South Sea Bubble.

The South Sea Bubble is often described as England’s first great financial crash. The spectacular rise and fall of the South Sea Company has been chronicled in detail elsewhere (see in particular Cowles, The Great Swindle; Carswell, The South Sea Bubble; and Balen, A Very English Deceit), but a brief summary will be given here for context. The South Sea Company was first founded in 1711 to trade with Spanish colonies in the Americas. Despite never having any particular success in this area, the company came to prominence in 1719 with a scheme to deal with the spiralling national debt, which had been worsened by decades of war. Under the direction of John Blunt, one of the company’s directors who became the driving force behind the Bubble, the South Sea Company proposed to take ownership of the national debt and convert it to South Sea stock, in which the public would be able to buy shares. The economics behind Blunt’s proposal were both complex and fantastical (see Cowles, The Great Swindle, chapter three and Balen, A Very English Deceit, chapter six for more detail) and the proposal faced a rocky passage through parliament, but with a liberal amount of bribery, it passed.

Blunt’s plans depended on an ever-increasing share price to generate profit and he worked tirelessly to inflate the value of South Sea stock. His plans worked and in the summer of 1720 South Sea mania gripped Britain. Everyone with any money to spare invested heavily in South Sea and the ballooning share prices made it seem as though there was endless money to be made. Stock also began to be sold on credit, a fairly novel concept in the early eighteenth-century, which allowed investors to buy far more stock than they could actually afford. In wake of the apparent success of the South Sea Company, numerous other ventures popped up to take advantage of the mania for investing. Schemes ranging from insurance, to land improvement, to extracting silver from lead, all clamoured for investment. Some schemes were genuine, others fraudulent, others just ridiculous, yet the public, caught in the spirit of the time, invested. These companies became known as ‘bubble companies’ by sceptics, a term which proved all too apt.

In autumn 1720, the bubble burst. Ironically, the crash was in part brought about by John Blunt himself, who persuaded the government to clamp down on other bubble companies to reduce competition for South Sea. Confidence in the stock market faltered and over the course of a couple of months, South Sea stock prices (along with many others) plummeted. The effects of the crash were disastrous, for individuals as well as the economy and government.

Thomas Bowles’ Bubble Cards were issued at the height of the Bubble, when endless schemes were trying to persuade investors to part with their money. Each card bears an image and verse satirizing a bubble company. The cards are functional as playing cards, with a full set of suits and numbers. At three shillings and sixpence, they were priced at the expensive end of mid-range prints and would likely have been purchased by the middling and upper classes (Clayton, ‘Book illustration’, p. 235). As well as the satire on the packaging, South Sea itself has a card, the knight of clubs, with the verse:

Come all ye Spendthrift Prodigals that hold/ Free Land and want to turn the Same to Gold;/ We’ll Buy your all, provided you’ll agree/ To Drown your Purchase Money in the South Sea.

The concept of political playing cards was not entirely new in the early eighteenth-century. Political propaganda cards appeared in late seventeenth-century England, primarily in opposition to the Catholic Church. The defeat of the Spanish Armada, the 1688 revolution, and ‘Popish Plots’ were all themes of playing cards that were printed at this time (Whiting, A Handful of History, p. 2 and Hoffmann, The Playing Card, p. 45). But the Bubble Cards are an example of a new trend in political and social commentary in the early eighteenth-century – satire. The eighteenth-century was the heyday of the satirical print and the South Sea Bubble helped to spur the development of British satire (Atherton, Political Prints in the Age of Hogarth, p. 1). Initially, many satires were imported from the Netherlands (Atherton, Political Prints, p. 1). Thomas Bowles, the printer of the Bubble Cards, purchased and sold The Great Mirror of Folly in 1720, a Dutch book of satirical prints of the financial crises enveloping Britain and the continent at the time (Hallett, The Spectacle of Difference, p. 61; France suffered its own financial scandal around the same time – for more see Cowles, The Great Swindle). But in the wake of the Bubble, local talent began to blossom. William Hogarth produced his first political satire following the Bubble, in 1721. Simply entitled The South Sea Scheme, the image shows the directors of the South Sea Company taking the subscribers for a ride on a wheel of fortune, while the devil dismembers Fortune, Honesty is broken on a wheel, and Honour is flogged (Wynn Jones, The Cartoon History of Britain, p. 18). Hogarth went on to produce other satires of the political aftermath of the Bubble, as did many others; one of the more famous is entitled The Skreen and accuses Robert Walpole of shielding those guilty of shady dealings during the Bubble (Wynn Jones, The Cartoon History, p. 18). The authorship of The Skreen is disputed – it is generally believed the attribution to Picart is false, and was made in order to evade prosecution (see record at http://prints.worc.ox.ac.uk/scripts/fullrecord.asp?location=XVI%3A+388).

A True Picture of the Famous Skreen, 1721

The popularity of graphic satire coincided with the growth of another cultural trend in eighteenth-century Britain – print collecting. Prints were not just illustrative matter, but covetable commodities in their own right, collected for information or decoration. A range of prints, from basic woodcuts to high-end engraved fine art images, could be found in printsellers, though political prints were often sold by shops which specialised in political material (Clayton, ‘Book illustration’, pp. 230 – 234). Collectors sometimes framed prints for display, but compiling bound albums of prints was also very popular (Clayton, ‘Book illustration’, p. 230). This is how George Clarke, our library’s great benefactor, chose to display his pack of Bubble Cards, pasted into an album along with portraits and other satires (such as The Skreen above). George Clarke was an avid print collector and left a collection of over 8,000 prints to the College Library. Clarke’s collection was largely a working collection to support his architectural interests and projects, with a heavy emphasis on architecture and antiquities, but he also collected other popular subjects of the day, such as portraits and reproductions of continental paintings. In addition, he was an early collector of English satire, collecting items such as the Bubble Cards and Hogarth’s early work. (For more on Clarke’s print collection, see Clayton, ‘The Print Collection of George Clarke at Worcester College, Oxford’.) Although the Bubble Cards were designed to be functioning playing cards, their presence in an album of prints suggests that Clarke never used them as such, seeing them instead as collectables or entertainment. It is fortunate for us that he did, as little of this kind of ephemera survives and it can provide a very different perspective on popular and political culture of the time.

Renée Prud’Homme (Assistant Librarian)

Bibliography

Atherton, Herbert M., Political Prints in the Age of Hogarth (Oxford, 1974)

Balen, Malcolm, A Very English Deceit: the South Sea Bubble and the World’s First Great Financial Scandal (London, 2002)

Carswell, John, The South Sea Bubble (Revised ed. Stroud, 1993)

Clayton, Tim, ‘Book Illustration and the World of Prints’ in The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain, Vol. 5 1695 – 1830, ed. Michael F. Suarez and Michael L. Turner (Cambridge, 2009)

Clayton, Timothy, ‘The Print Collection of George Clarke at Worcester College, Oxford’, Print Quarterly Vol. IX No. 2 (June 1992), pp. 123-141

Cowles, Virginia, The Great Swindle: the Story of the South Sea Bubble (London, 1960)

Hallett, Mark, The Spectacle of Difference: Graphic Satire in the Age of Hogarth (New Haven, 1999)

Hargrave, Catherine Perry, A History of Playing Cards and a Bibliography of Cards and Gaming (New York, 1966)

Hoffmann, Detlef, The Playing Card: an Illustrated History (Leipzig, 1973)

Whiting, J.R.S., A Handful of History (Totowa, 1978)

Wynn Jones, Michael and McDermott, J.A., The Cartoon History of Britain (London, 1971)

Pingback: Remembering 1720 in 2020 | Treasures of Worcester College